05.06.2025

I like to walk in a circle rather than up a line and back, so on this day I set off on a four hour clockwise walk around the ruin of the Ding Dong Mine Engine House. It would remain in view like a beacon of reassurance in a hostile landscape of fern covered mine shafts. There are twenty two of these scattered over the North Downs, an area that had been busy in the extraction of tin for as far back as the Bronze Age. What remains for us today is a rich variety of Megalithic monuments.

All around the Ding Dong Mine

On the western edge of my circle is the peculiar Men An Tol, a donut shaped stone on it’s side with two flanker uprights and a number of fallen stones hinting at a one time large circle complex. The donut stone’s hole is smooth and almost perfectly formed, so was it natural, skilfully sculpted or worn by the passage of small children through it ? Stories go that children were placed through the hole to cure them of rickets and tuberculosis. This medical phenomenon also stretched to the cure of orthopaedic issues and infertility in adults. Looking at the size of the hole it seemed unlikely that a fully grown adult would get through it without getting stuck. A couple arrived as I was there and I waited for one of them to prove me wrong. I was left disappointed but they did take photos using the hole as a frame much like a fairground ‘peep board’. Then my mind wandered to the tradition of ‘Gurning’ in the small Cumbrian town of Egremont, but lets not go there !

I moved on up the track to find a more discreet and lonesome standing stone in a delightful field of yellow meadow flowers. At first glance the two metre high stone looked unremarkable until I walked around it. On it’s northern side were traces of a Roman inscription, two thousand years on from the stone’s placement which reads ‘RIALOBRANI CUNOVALI FILI’ ‘Royal Raven of the Glorious Prince’, a curious tag of re appropriation I thought. It’s a wonder that more ancient stones haven’t fallen foul to the mallet and chisel.

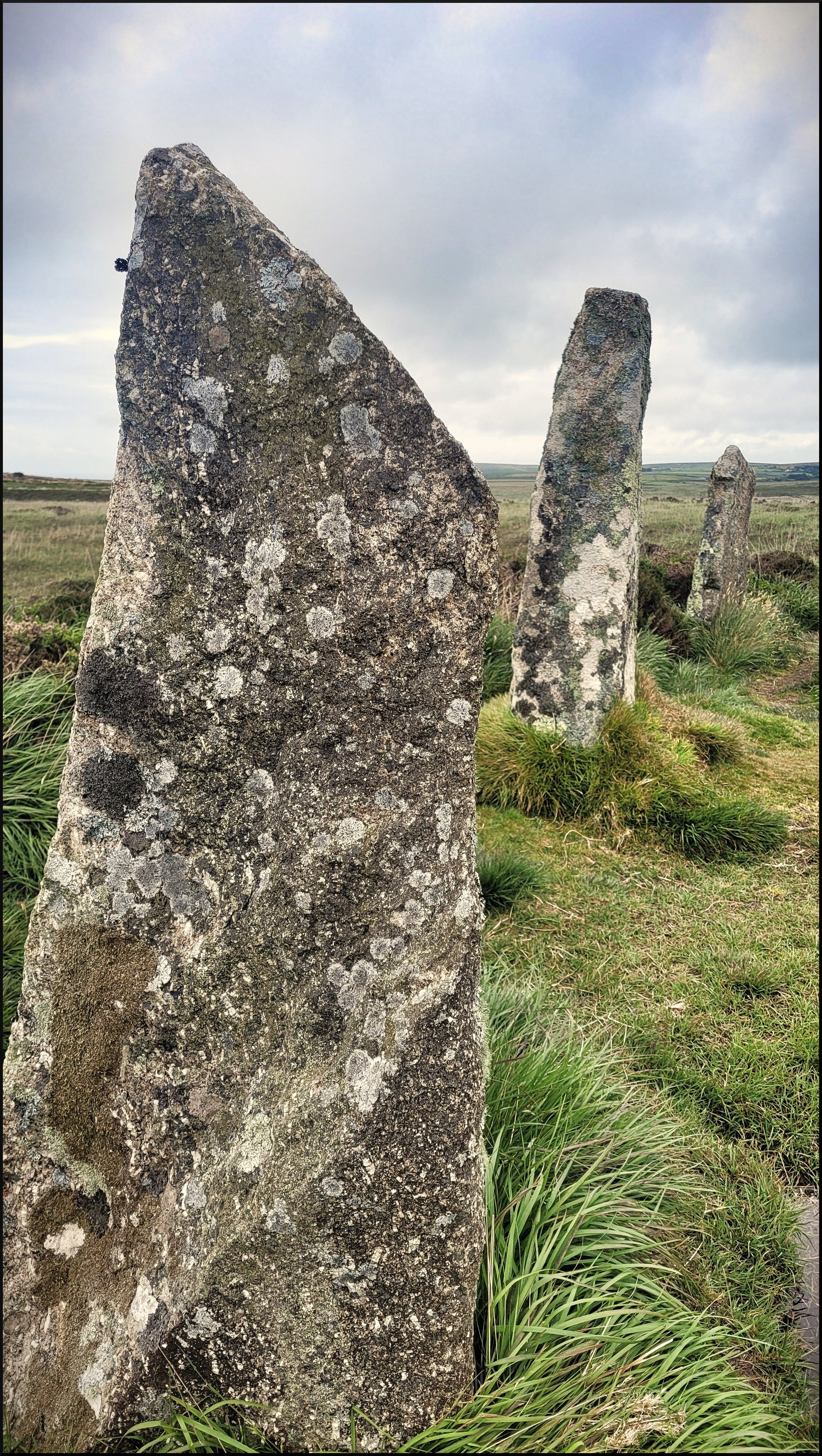

The farm track continues north and transforms into a narrow path where I meet an elderly woman in a billowy dress with a gnarled stick and a fearsome attitude. We walk together and she tells me she’s a Lanyon, from a long established family dating back to the Knights Templars. She’s on patrol protecting the moor from off road bikers and anyone else who threatens this precious landscape. It’s her daily duty she says and will sit in her car for hours keeping watch. She points all around and speaks of the ley lines in the area and says as we reach the stone circle of Boskednan that we were standing on one. She had felt strong energies from them in the past, but raising her finger and pointing to the circle she proclaimed it to be ‘dead’ and had felt nothing from it.

Boskednan was none the less impressive and as Paula Lanyon disappeared off in the direction of he Engine House I was left alone to immerse myself in the circle and feel something maybe? I circled the circle in another clockwise direction feeling the rough outer and smooth inner faces of each stone. This was a feature common to stone circles all over these islands, Brodgar on Orkney being one classic example. Also common and to the Cornwall region is the number of stones, ranging from nineteen to twenty two. Boskednan had an original nineteen but only eleven remain with the largest at the north west arc of the circle. This makes it a prime candidate for lunar associations with a distant carn as a possible reference point. The longer I stayed here the friendlier this circle felt but there was no resonance, no spell forthcoming, no tingle or knot in my stomach I had felt elsewhere. I left it for others to feel it’s energies but I was reluctant to condemn it as ‘dead’.

My mind was not on my charted course and soon i was cutting through dense ground cover to get over to the right path. I was lucky enough to look down at the right time to see a small coiled Adder in front of me. It turned its head to watch me as I stepped over it. This did the job of focusing my thoughts and I vowed to stay on the path from here onwards.

My next encounter lay in a clearing of waist high ferns on a hill overlooking St Michael’s Mount at the top of my circle. Mulfra Quoit for all it’s charm was lacking an essential component that prevented it from standing proud, a forth upright. Consequently it’s absence had caused the slippage of the capstone that was leaning lazily on two of the remaining three uprights. It had none of the grandeur of Zennor Quoit (see 03.06.25) and provoked in me a feeling of sympathy rather than awe. I speculated at a possible turn of events for the missing crucial upright. Had it been removed by someone for some purpose before it’s protected status had been granted ? Like the recent felling of a famous tree the consequences had been conspicuously grave. Early antiquarians would have had a shot at correcting the aberration if there were the means to do so, but there were no stones present that resembled the now redundant remaining three. It began to rain hard as I made my way down the hill with the shoulder high ferns soaking me from head to foot.

I had now lost sight of the Engine House as I walked the narrow high hedged lanes south through the hamlets of Mulfra and Trythall. I could see the Downs ahead and then the familiar outline of the chimney appeared on the horizon. I passed through a farm and a field with three frisky horses galloping around me and showing off. I crossed a high wall and was back in thick moorland cover with the Engine House right in front of me. It loomed large above me as I passed it’s eastern side. A branch path off the track took me east through the Bosiliack Bronze Age settlement. Mostly hidden in the summer’s undergrowth the hut circles shared the landscape with the covered and treacherous mine shafts. The well preserved circular Bosiliack Barrow came into view with raised curb stones and cobbled infill supporting a short open passage chamber at the centre that would have faced the mid winter sunrise. It was one of the smallest Cairns I had come across and had the hallmarks of a well considered restoration. I was hoping to see more of these barrows on the Scilly Isles in a few days time.

My circle was almost complete but for one last monument, the Lanyon Quoit. Was this where Paula was heading two hours previously, her namesake dolman and one that stood as intended ? It looked proud and defiant as I approached it, with a colossal capstone held high by three ‘going nowhere’ uprights. It was a tour de force of balance and poise with the capstone jutting out over it’s supporting stones like the peak of a cap. It was as solid an ancient structure as I’d seen in Cornwall, but there was a twist in the history of Lanyon Quoit that began in 1815 when the whole lot collapsed in a storm and remained that way for ten years before it’s restoration. Some Quoits get all the luck !

The road nearby took me back up to Rosie, parked a mile away. My circle was closed. I had dodged the mine shafts and adders and journeyed through a rich landscape of the Bronze Age.