The jewels of Bodmin Moor

28.05.2025

The southern part of Bodmin Moor near the Village of Minions has a complex of monuments clustered together within a short distance of each other. I was keen to see a trio of stone circles there known as The Hurlers which had intrigued me whilst reading Aubrey Burl’s ‘The Stone Circles of the British Isles’. A short walk up from the car park brought me straight to it and to a conical standing stone that was once part of an avenue to the circles beyond. From here the arrangement looked jumbled and confused, but as I got near the distinctive arcs of their layout began to make sense. All three were over one hundred feet wide and made up of similar sized granite with many of them being straight sided shaped blocks with flat tops. Others were worn and riven and more characterful. On the south west edge of the central circle stood a Tri stone. These are common to Bodmin’s circles and vary in placement at each site depending on the alignment of the sun and moon. This one however was distinctly diamond shaped. As I wandered amongst them I thought of how fashioned these stones were and how their creators had possibly drawn inspiration from the natural rock formations in the landscape around. On the horizon to the north east was Stowe’s Pound, with it’s Tors of weather sculpted outcrops.

Just beyond the northern circle I sat on a grass bank and drank in my surroundings. The chimneys of tin mine engine houses rose from the moorland to the south. I watched a couple with their small dog enter the central circle and perform aerobics, making slow wide arcs with their arms reminiscent of some long lost ritual practice. It felt timeless for a moment and conjured a vision of ancient ceremony in my imagination.

I walked back through the complex touching some of the stones that had spoken to me. To the south west stood the Two Pipers, named after two unfortunate musicians who like the Hurler’s ball throwers had been turned to stone for playing on the sabbath. Five feet in height and six feet apart, they struck me as quite comical. Being rough worn and vaguely figure like, one of them seemed to have a contented smile. ‘Our punishers have long gone but we are still here’ it seemed to be saying.

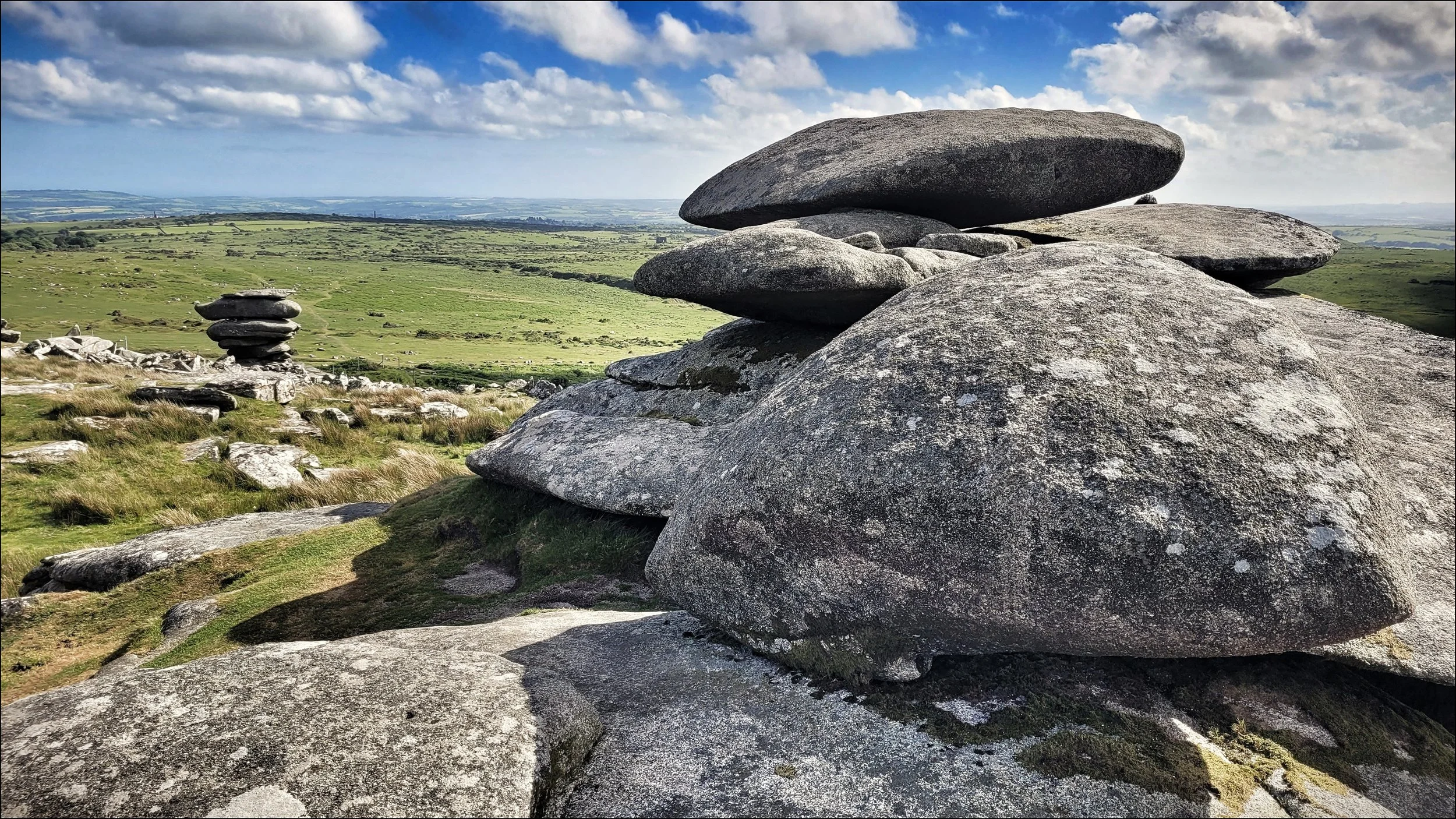

I took a path west that curved to the north to Stowe’s Pound, a large Tor of astounding weathered rock formations. A steep climb up through large rocks brought me to the summit amongst the smooth stacks of pancake shaped boulders. This had once been the site of a Bronze Age settlement and the thick perimeter wall of piled stones was still visible surrounding the Tors. This would have been a harsh but magical place to live with the large outcrops offering some protection against the cold winter winds. Walking amongst the enormous natural sculpted rocks I felt certain this would have been a fortress of great status and inspiration with the security of three sixty views all around.

The last monument in the area was Rillaton Barrow, a quatre of a mile to the east. It was a bit tricky to find at first, being quite shallow and surrounded by small hillocks. The clue to finding it was a low passage entrance with a stone lintel hidden on it’s eastern side. When I found it I was amazed how undisturbed it looked despite what had been unearthed inside. In 1837 along with skeletal remains a gold cup had been found here. Prior to it now residing in the British Museum the cup had been the subject of a right royal plunder, as it was found in the possession of George V, who was using it as a receptacle for his collar studs.

I returned to the Hurlers to sit on the grass bank. It was early evening and with no one around I enjoyed the silent solitude and allowed my imagination to take me back in time.

Recharged, I decided to extend my walk up the road to the Longstone. On my way to it I had the pleasure of seeing two farmers on horseback rounding up their stray sheep. I waited till they skillfully gathered them together and watched them disappear onto the moor to the west. It was a sight I would have expected across the Atlantic or down under and not in Cornwall. The Longstone stood not far from the road. Also known as Long Tom it rose to a height of nine feet and leant slightly to the east. It had at some point been subject to christianization, with it’s stand out feature being the circular motif of a cross at the head of the stone. On closer inspection I found what looked like a Chinese character cut into it’s northern face. It was identical to a mark I’d seen on the Bone Stone at the Drizzlecombe complex on Dartmoor, apparently graffiti left by visiting Chinese students in the 1950s.